BANK program prevents evictions, keeping Dwelling Place residents housed through sudden crises

Donor support is needed to sustain BANK, which prevents evictions through one-time rental assistance and services that build lasting housing stability.

Staff members at Dwelling Place of Grand Rapids watched a painful pattern repeat itself over the years.

After long waits for housing and years of instability, residents finally got an apartment. They moved in with relief, and often with a history of homelessness, trauma, disability, or domestic violence. Then a car broke down. A temp job cut hours. A medical crisis hit. One missed rent payment became two.

The eviction clock started ticking.

And too often, people who had fought so hard to get housed slipped right back into homelessness.

“People think the hard part is getting someone into housing,” says Alonda Trammell, chief programming officer at Dwelling Place. “But the real work starts once they get the housing. Housing stability touches so many other things: health care, mental health, safety. For a lot of people, this is their first housing in forever. We become family to them.”

This is what inspired BANK, short for Bringing Assistance to Neighbors through Kindness. The rental assistance fund was created not just to keep people in their homes for one more month, but to connect them to the support they need to stay housed long term.

Early success

The BANK program launched this summer after Dwelling Place received a grant to strengthen its eviction-prevention work. The nonprofit already offered classes such as financial literacy and anger management, but staff also saw an urgent need for something more direct. They wanted to provide tailored programs to help residents who are one difficult month away from losing their homes.

“We wanted to build a fund to provide a one-time rental assistance payment for residents who were behind in rent,” says Regina Bradley, who helped design the program along with grants coordinator Jesse McCormick. “The challenge was making it equitable and fair, and making sure it was sustainable.”

They started small. The pilot launched with $10,000 earmarked for residents in some of Dwelling Place’s highest-need properties, communities that serve people who were chronically homeless, have disabilities, are seniors, are survivors of domestic violence, or are part of low-income families.

Within four months, the entire $10,000 was gone. But the impact went far beyond the dollar amount.

They had 28 applications, and 19 households were approved for assistance. The average grant was about $482 per household, enough to catch people up on rent and head off eviction.

According to Dwelling Place’s calculations, those modest investments translated into more than $78,000 in cost avoidance. That is based on the expense of what it would have cost the organization to turn those units over and re-lease them.

“We’re reinvesting those savings directly back into Supportive Services so we can keep doing this work. It’s a cycle that keeps people housed and keeps our services strong,” says Ali Conley, Dwelling Place’s strategic partnerships and fundraising manager.

Every one of those 19 households remains stably housed.

Deeper than rent payment

Before BANK, resident services coordinators (RSCs) did what they could. This might mean referrals to community agencies, connections to churches that offered one-time help, payment plans with property managers. But the support was scattered, slow, and often out of Dwelling Place’s control.

And there was another challenge: under HUD rules, residents in independent housing can’t be required to work with support staff.

“In our buildings, people don’t have to engage with their resident services coordinator,” Bradley explains. “This is their housing. They can do what they want. But we were evicting people for nonpayment who weren’t engaging because of their mental illness, substance use, or other struggles. We needed a way to get them to the table.”

That’s where BANK comes in. The rental assistance itself is important, but staff see the money as a “carrot.”

To qualify, a resident must:

- Be referred by property management after falling behind on rent

- Work with an RSC to complete an application

- Create a housing stability plan that looks at why they fell behind and how to prevent it happening again

- Complete a budget with staff

- Agree to pay the next month’s rent themselves, showing “skin in the game”

A scoring rubric helps to assure fairness and consistency in who gets funding. If approved. The payment goes directly from the BANK fund to the property, stopping eviction procedures.

“We realized the money isn’t the real magic,” Bradley says. “The magic is that it gives us a reason to sit down and talk honestly about what’s going on: mental health, substance use, helping adult children, whatever is underneath the missed rent. It opens the door to the services.”

Crystal Cunningham, a resident services coordinator who works at two Dwelling Place properties, sees that transformation up close.

“There’s so much shame around asking for help,” she says. “We use this fund to take away the shame and say, ‘We’re here to listen, not judge.’ Once that relationship is there, people are much more likely to come to us before things spiral.”

‘It’s the relationship’

Lisa Blackburn, a senior resident services coordinator who has been with Dwelling Place for 16 years, remembers one resident, who was featured in the organization’s year-end appeal.

The resident had recently moved in after being homeless. She was working through a temp agency, which meant her hours and income were unpredictable. It didn’t take long for her to fall behind on rent.

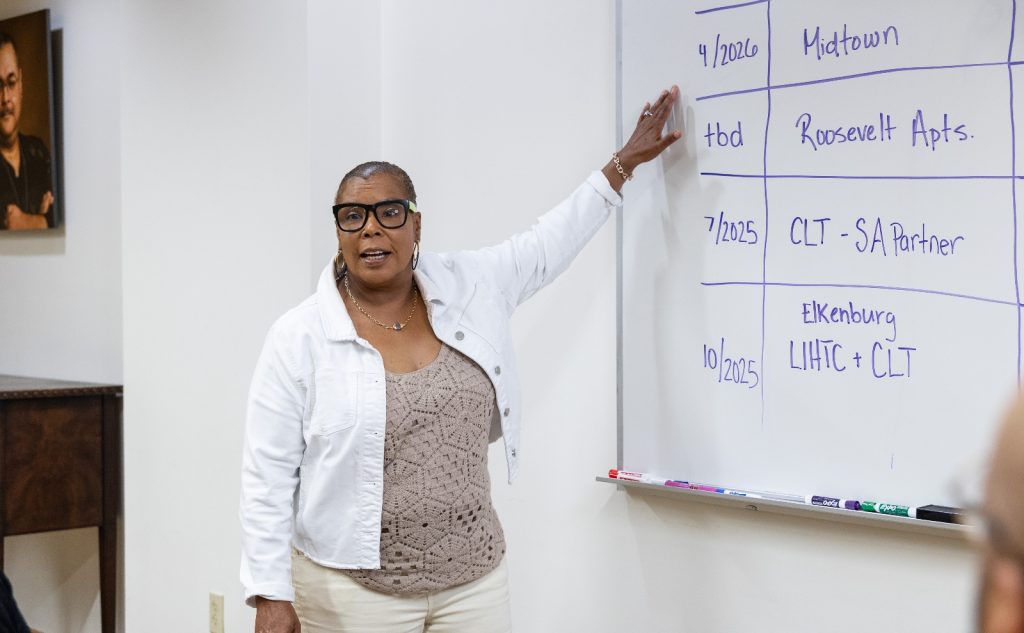

services coordinator. (Photo by Tommy Allen)

“She came into my office overwhelmed, in tears,” Blackburn recalls. “She told me, ‘I just got out of the streets. I don’t want to go back to the streets. I don’t know what to do.’ She had her grandchild with her. She was trying to hold everything together.”

While the resident knew there was a resident services coordinator in the building, but she didn’t really understand what that role meant, or how much support was available. Blackburn sat with her and explained the BANK program, how it worked, and what the resident would need to share to apply.

At first, the resident hesitated.

“She’d been through a lot. Trust is hard when you’ve had your life turned upside down,” Blackburn said. “I told her, ‘Trust me. I’ve got you. I’ll advocate for you.’ Eventually, she agreed to let me help.”

Blackburn gathered the information, sent the application to Bradley and McCormick, and waited.

When the approval came through, the resident could hardly believe it.

“She was so happy, just overwhelmed,” Blackburn says. “She told me, ‘Lisa, you’re like a god.’ I said, ‘No, I’m just doing my job.’ But to her, it meant she wasn’t going back under a bridge. She could breathe again.”

Since then, the resident has continued to check in regularly, emailing Blackburn with updates, questions, and worries before they become crises.

“That’s the point,” Blackburn says. “It’s not just one payment. It’s the relationship that grows from it.”

Breaking a cycle

Trammell, who has been with Dwelling Place for more than 30 years and started as a resident services coordinator, thinks of BANK as not just about numbers. It’s about stopping a destructive and expensive cycle.

“When someone gets evicted, we’re not just talking about losing an apartment,” she says. “People lose their medications, their identification, their documents. They get re-traumatized. They go back into systems, shelters, jails, emergency rooms, that are already overwhelmed.”

Cunningham hears about those experiences from residents. One man she works with had been living on the edge for years. His wife had a stroke and was going through rehab. He was diagnosed with cancer. As a result, his bills piled up, and he fell behind on his rent.

“He was drowning,” she says. “He told me flat out, before this kind of support, he’d had to do things he really didn’t want to do just to get by.”

Through BANK, staffers were able to quickly cover his arrears, connect him to community resources to stabilize his finances, and enroll him in budgeting classes at the library next door.

“At first, he wanted nothing to do with it,” Cunningham says. “Now he’s going to classes, reading again, understanding his finances. His whole outlook is different. His mind is brighter. He’s not recycling back through the same systems.”

That “recycling” is exactly what Dwelling Place is trying to prevent, both for residents and for the broader community.

“Supportive housing reduces recidivism back into homelessness and the criminal justice system,” Cunningham said. “It reduces substance use, ER visits, all of it. As a taxpayer, that’s huge. As a human being, it’s even bigger.”

Simplified system

BANK has also streamlined its procedures compared to many public or charitable assistance programs.

Cunningham has watched outside charities and federal programs tighten requirements as funding gets stretched, adding documentation and delay to processes that were already slow.

“Some of those programs have so much paperwork and such long timelines,” she said. “Meanwhile, a resident is sitting there with an eviction notice.”

With BANK, the steps are intentional but simple. The resident, property management, and RSC all play a role, so the decision-making happens inside Dwelling Place.

“The application is low-barrier by design,” Cunningham says. “We ask for what’s relevant and necessary, nothing more. We’ve removed three or four extra portals that other programs use. That’s what makes it unique.”

Conley points out that this design also benefits donors.

“When we talk to supporters, we can look them in the eye and say, ‘Your donation is keeping people housed, directly,’” he said. “The dollars go straight to rent, and the savings stay in Supportive Services.”

Trammell, who describes herself as “very resident driven,” says BANK has given staff another tool to live out the mission that has kept her at Dwelling Place for three decades.

“I feel a sense of responsibility to do this type of work, to be in these spaces,” she said. “We’ve got a lot of changes happening with government and the economy. But that doesn’t mean the day-to-day stuff people are faced with goes away.”

For her, housing is never just about a lease.

“Sometimes people think, ‘Oh, you just get them housing.’ No,” she said. “The real work starts once they get the housing. Everybody needs something different. Our goal is to respect and honor the people who live in our buildings, and make sure they have what they need to thrive.”