Breaking the cycle of homelessness: Dirt City Sanctuary’s community-centered recovery philosophy

Dirt City Sanctuary aims to care for individuals experiencing substance use disorders and homelessness by providing housing, jobs, community, and individualized support.

“I was that dude who no one thought could ever get clean. I was doing between $300-$500 worth of drugs every day and going to jail constantly,” says Tyler Trowbridge, co-founder of Dirt City Sanctuary. “I was addicted to heroin, cocaine — pretty much every drug possible. It was to the point I was going to die and something had to happen.”

But recovery to Trowbridge seemed impossible. He suffered from chronic homelessness and had been using drugs for 15 years.

Sara Schade, executive director of the drop-in center Unlimited Alternatives, knew Trowbridge for many years and had been going in circles trying to aid in his recovery. “One of the things that Tyler was so good at was going out on the streets and getting money, so it was hard to have that real, good motivation to get into recovery,” Schade says.

After Schade did an interview on the opioid epidemic for WOOD-TV8, she recommended they speak with someone still actively using, like Trowbridge. “That day, we were sitting there and he was really nervous about doing it. I said, ‘You never know, somebody might see the story, want to start a go-fund me account and change your life.’”

Sure enough, the night it aired, Stacy Peck, a former classmate of Trowbridge, watched the segment that showed Trowbridge homeless, panhandling for money, and shooting up drugs in a bathroom with frostbitten hands. “The part that got me the most was the fact that he was maybe five miles from where I live and this was someone that I went to high school with from a small town,” Peck says.

Even though Peck and Trowbridge had not been very close in high school, Peck was heartbroken to see a familiar face in such pain. Unsure of how best to help, Peck messaged Schade on Facebook and later met Trowbridge at Unlimited Alternatives.

“I told him, ‘If you really want to do this, I’ll help you get housing, get treatment, get a job, and we’ll just go through all these things that are keeping you in this cycle one by one and get rid of them,’” Peck says.

Reconnecting with Peck gave Trowbridge the lifesaving hope and support he needed. “The exact words I had said to her were: ‘Well, just don’t give up on me and we can do it,’” Trowbridge says. The next day, Trowbridge started treatments. Within two weeks, he secured a job and found an apartment — all with Peck by his side never giving up.

After joining forces on February 26, Peck and Trowbridge wanted to support other people with their recoveries throughout West Michigan. Along with Wendy Botts, whose son died from a fentanyl overdose in 2017, these three co-founders teamed up to create the nonprofit Dirt City Sanctuary.

“We decided to find other people like me — people who society has pretty much forgotten about, people who have no support or no hope — and try to help like she helped me,’’ Trowbridge says.

While a 2008 survey by the United States Conference of Mayors found substance abuse to be the largest cause of homelessness for single adults, the National Coalition for the Homeless stated that in many instances, substance abuse is a result of homelessness — rather than a cause — since many people who are homeless see it as the only way to cope with their situations. “It’s somewhat rare that somebody has been out on the streets and there isn’t an underlying substance use issue,” Schade says.

But the real concern hides underneath the substances. According to the Michigan chapter of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, co-occurring substance-abuse disorders are found in approximately 50 percent of homeless adults with serious mental illnesses. Schade added that, although co-occurring disorders are prevalent in the Grand Rapids homeless population, most of us only look at the substance side of the problem and forget to think about the mental illnesses that need to be addressed.

“Mental health issues are being treated with substances, but we don’t really get a chance to see the mental health issues because the substance use disorder is louder than the rest of it,” Schade says. “If it’s a major trauma that they are dealing with, then they have PTSD that got them on the streets, now they are getting recurring trauma from living on the streets. We’re in Michigan so when it’s cold, it’s really hard to go to sleep without being drunk. It’s this never-ending cycle.”

Now in the fundraising phase, Dirt City Sanctuary aims to care for those individuals experiencing substance use disorders and homelessness by providing residents with their own housing, a job that gives them purpose, a community to cultivate relationships, and individualized support to help address any underlying trauma or mental health issues.

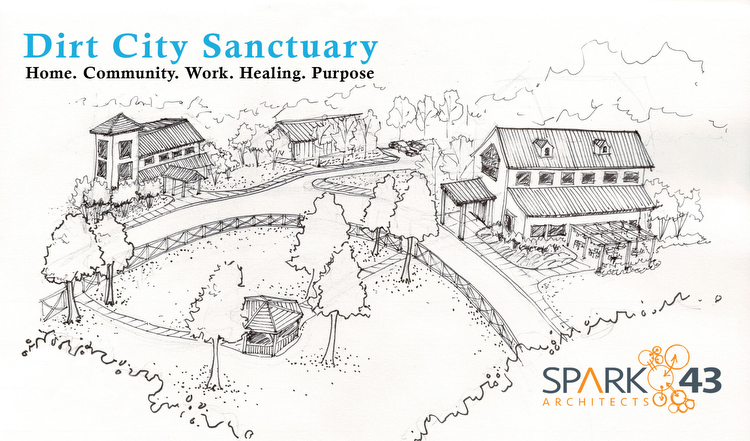

Scheduled to build two campuses in Kent and Newaygo Counties, Dirt City Sanctuary’s building project includes three different housing options.

For those who have been chronically homeless and have a substance use disorder, participants will be placed within the City of Grand Rapids in housing that will not have barriers to qualify. “We’re not going to say you have to be sober to live here. We’re going to say you’re a human being and therefore, you deserve a place to live,” Peck says.

Located on Dirt City Sanctuary’s main campus, the second housing option is for people actively seeking recovery. Consisting of three farm-style homes, there will be the choice of men-only, women-only, and co-ed houses. Each will be designed with a communal space on the main floor that includes a living room, dining room, kitchen, library, bathroom, and laundry room. Every person will also be provided with their own studio apartment on the upper levels.

Along with the farm-style homes, there will also be two barns, one that will house animals, and the other that will be used as a multi-purpose event space. John Whitten, principal architect for the building project and owner of Spark43 Architects, said spending time with animals not only will help keep members’ minds away from drugs, but it will also help them learn to care for another life.

“Unlike people, animals tend to provide unconditional love. A lot of people struggling with substance use disorder, or what most of us would simply call addiction, have burned most, if not all, of their bridges with their families and friends. Animals provide a bonding opportunity in a time of extreme vulnerability,” Whitten says.

Through workshops, meetings, and fundraisers, the multi-purpose event space also hopes to be a room in which the entire community of West Michigan engages and connects with the participants in the program. “Wouldn’t it be incredible for outside organizations to spend time on a campus like this, meet our neighbors, learn about what they are doing, hear their stories, and provide a venue for dialogue that ultimately humanizes a societal crisis that has been largely dehumanized in the broader conversation?” Whitten asks.

While Whitten urged for community involvement, though, he was aware that there are negative stereotypes against people experiencing homelessness and substance use disorder. Before he met Trowbridge, he admitted he was guilty of similar thoughts.

“There is so much stigma, misinformation, and lack of understanding around addiction and the people who struggle with substance use disorder that this place has the ability to foster dialogue in addition to everything else,” Whitten says. “I was one of those people that had a whole bunch of preconceived and incorrect notions about addiction and who the person who might struggle with addiction is. I distinctly remember driving past Tyler several times on the south side of town, and I could not have been more wrong about him.”

Community involvement is not only vital to Dirt City Sanctuary, but also to the recovery process. Trowbridge explained that having supportive relationships is one of the most important keys to success in recovery.

“People need the support. That’s what’s missing in a lot of people’s lives. That feeling that someone gives a shit about them. That feeling that someone will miss me if I’m gone. It’s that feeling that someone will go out of their way and take that extra step to help you. For me, that was everything,” Trowbridge says.

While Dirt City Sanctuary anticipates housing participants anywhere from six to 24 months, the nonprofit intends to make its third residential option sustainable for long-term recovery. With help from Spark43 Architects, tenants will be given the opportunity to build their own homes out of shipping containers.

In addition to teaching highly-marketable vocational training to residents, Whitten explained that there are many benefits to this sober-living community. “The possibility of building and owning a home provides a significant sense of pride and a ton of incentives for our neighbors to stay the course with their recovery. At the end of the day, they would not only have something to be proud of, but a significant financial asset as well,” Whitten says.

Since the nonprofit aims to help residents get back on their feet financially, participants will not be required to pay anything for the first two months. “We want to be a place where if you don’t have money, that doesn’t stop you from coming into our program,” Peck says.

Because finding employment is also an important aspect to its plan, Dirt City Sanctuary’s goal is for all members to be working within the first few weeks of entering the program. To achieve this, the nonprofit will offer opportunities, such as paid training to learn skilled trades and employment on its campus or through its community partners. This way, Peck explained that not only will residents be able to pay the rent after those first two months, but it will also give them a sense of purpose.

Focusing on providing people with a new way to recover, Dirt City Sanctuary hopes to achieve an honest environment where participants can admit if they slipped up and move forward to achieve long-term recovery. As someone who celebrated her 11th year off opioids in December, Schade wants people to understand that relapse is a part of the recovery process and therefore, should not be punished.

“In most programming that you get into, if you end up relapsing once or maybe twice, they kick you out of your treatment. It’s the only disease that we treat like that. If you are a diabetic and you don’t take your insulin for a few days and eat too many sweets, your doctor isn’t going to kick you out,” Schade says. “We need to stop living in a system where you are penalized for having a symptom of your disease — which is relapse.”

According to Trowbridge, to treat people with a one-size-fits-all approach is not a recovery-centered method. Because of this, Dirt City Sanctuary will create an individualized recovery plan for each participant. “Everyone has a different perception of life — different feelings, different needs, different wants and different styles — and you have to cater to that,” Trowbridge says. “You can’t expect people to be successful when you’re trying to make them do a program that’s meant for someone else.”

To celebrate Trowbridge’s first year in recovery, Dirt City Sanctuary will be hosting “Building Bridges: Recovery Through Community Gala” on February 26. For more information, visit https://dirtcitysanctuary.org/building-bridges-gala/

Photos by Adam Bird of Bird + Bird Studio.