The museum as a classroom

Educators increasingly rely on the Grand Rapids Public Museum as a dynamic classroom where students can “wake up” history, learn through listening, and find that curiosity and a sense of belonging can be cultivated together … and sometimes through the sharing of individual stories.

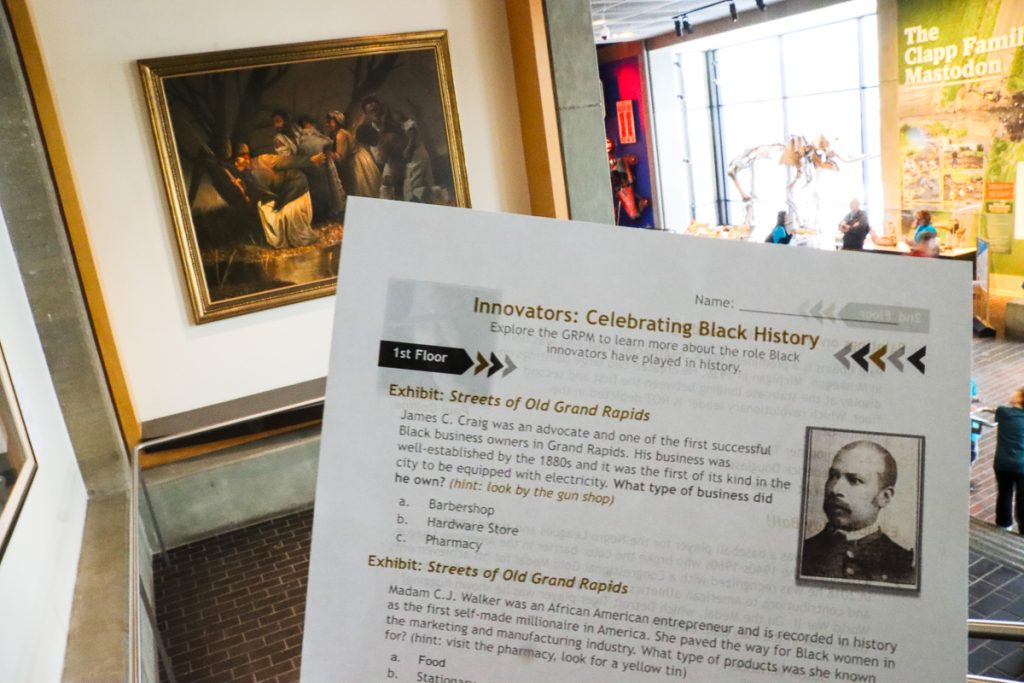

Students wandering through the Grand Rapids Public Museum (GRPM) at some point find themselves stepping into the Streets of Old Grand Rapids. Suddenly, the past starts talking back.

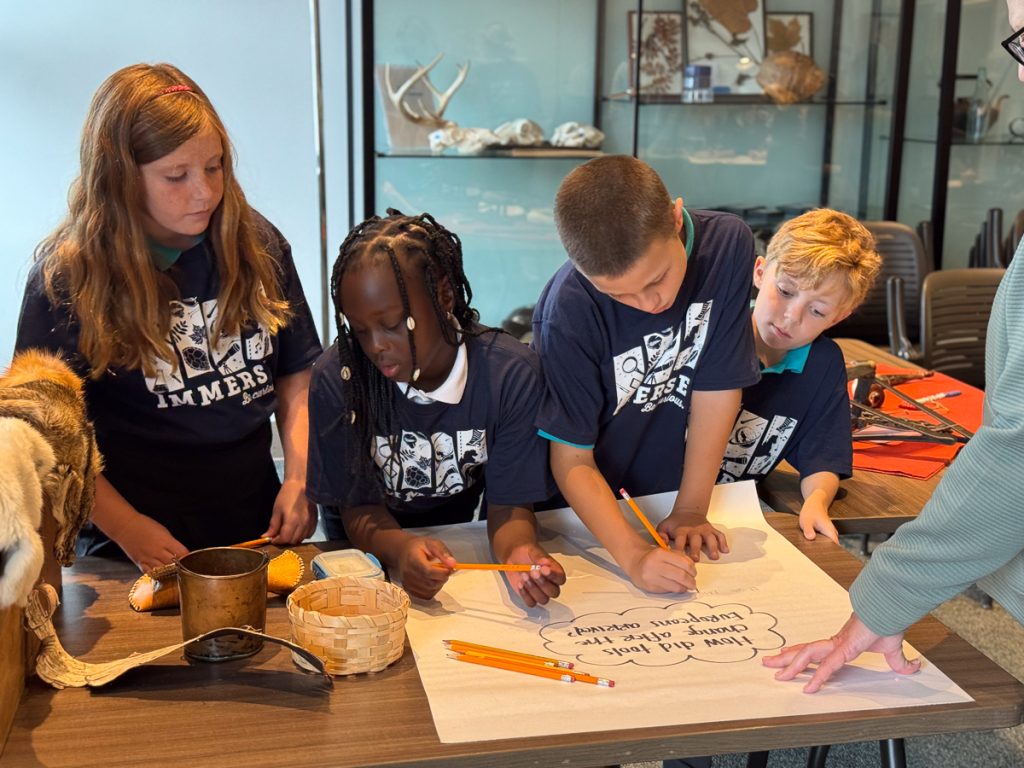

One of the Grand Rapids Public Museum’s guided programs is in action. Students are encouraged to use tablets to “wake up” characters in the exhibit, from shop owners to community members, who speak to them and send the students on a scavenger hunt for clues, deepening the opportunity for education beyond pure observation.

A barbershop owner, for example, might ask them to search for an item, and the students fan out, hunting together, comparing notes, and learning as they move through the museum.

What makes the program tick isn’t just the tech; it’s how museum educators adjust the experience in real time, shifting prompts and challenges so it works for second graders and sixth graders using the same core structure. Stephanie Ogren, GRPM’s vice president of science and education, says teachers consistently tell the museum how well staff “adjust it to the level of the students,” and that responsiveness is part of why this particular program is so in-demand.

That “meet you where you are” mindset shows up again and again in how Ogren talks about what the museum is trying to do for West Michigan learners.

She returns to a simple truth: students don’t all learn the same way, and they most certainly don’t all arrive with the same cultural reference points. If any museum wants to inspire curiosity and deepen understanding, it has to design experiences that invite a wide range of learners into the room.

A public museum as a public benefit

East Kentwood art teacher Le Tran has watched that invitation take root firsthand through GR Stories, a museum-connected project that asked students to contribute their family histories. The program was reported in Rapid Growth’s “Students preserve stories of Vietnam War survivors” by Shandra Martinez.

“When I hear ‘public museum’ or ‘public library’ or ‘public school,’ I think of an institution that is accessible to everyone,” Tran says. “The concept of a public space for all is beautiful. Simple yet beautiful.”

But what makes Tran’s experience especially powerful and relevant for educators is something many of us forget: not every student grows up knowing what a public museum is, or believing it’s meant for them.

Tran explains that she and many of her students “did not grow up in America,” where public entities, like the GRPM, serve as shared community resources and where community members can contribute to the historical record. That context shaped how she introduced GR Stories to her students and why she framed the museum as a living place, ever evolving, where community history is built by the community itself.

Tran invited students to share their families’ immigration stories to mark the 50th anniversary of the fall of Saigon, an act of learning, yes, but also of civic belonging.

Two student reflections, shared by Tran, showcase what can happen within a student when a museum experience becomes more than a field trip and becomes a “real audience” moment.

Christina Le, a student from East Kentwood, explained how this museum project changed her connection to her Vietnamese heritage. What was mainly passed down through family stories suddenly became something she could explore, study, and present as part of a broader cultural history.

“It wasn’t just an assignment,” Le says. “I was preserving and sharing a narrative that may otherwise go unheard.”

Another student, Sophia Cao, says the project helped her understand her Vietnamese family’s sacrifices in a whole new way, and that this realization ultimately changed how she viewed her grandparents.

Tran shared other stories she had heard, connecting the deeper “belonging” layer directly to how her students processed the experience.

Suddenly, these personal stories, according to Tran, began to reveal a vital piece: students realized they weren’t alone, zeroing in on the opportunities to flourish as they understood just how a story can be told, and recognized that being treated “like everyone else in the room” can be its own kind of quiet welcome.

Designed for real classrooms, expanding bandwidth

GRPM seeks to assist teachers through practical initiatives that alleviate difficulties and enhance confidence, especially for those visiting a museum for the first time.

Ogren describes educator-focused preview nights that offer teachers early access to major exhibits and practical tools they can use in their classrooms. For instance, during a recent exhibit, teachers attended a special night where they received a new classroom book related to the exhibit, along with field trip guides and curriculum connections tailored to their education needs.

Those nights also serve a second, deeper purpose: community.

Ogren described these nights as a space where teachers can connect with each other, share what’s working, and feel recognized, all the while museum staff listens closely to what teachers actually need.

The listening loop is crucial. For example, Ogren says teachers wanted more guidance structures in the exhibits, but the museum cannot provide this in every area. Still, this feedback prompted new strategies, such as scavenger hunts and guide-style tools, to strengthen the connection among teachers, students, and museum educators.

Belonging is a design choice

When Ogren talks about belonging, she doesn’t stay in abstraction. She points to an approach rooted in Universal Design for Learning and credits a wide web of partners, including disability advocates, faculty at Calvin University, and occupational therapy students at Grand Valley State University, for helping keep programs current and inclusive.

In practice, that can look wonderfully simple: instead of requiring only written responses, a worksheet might allow students to draw; an educator might invite students to “turn and share” in pairs; students can demonstrate understanding in ways beyond language.

Ogren notes that the museum experience often feels “not as rigid as it may be in school,” which can make it easier for students to share ideas even when language isn’t their primary means of communication.

The Museum School model

GRPM’s partnership with Grand Rapids Public Schools includes the Museum School embedded within the museum, and Ogren offers a behind-the-scenes example of what that makes possible.

Museum School students, she explains, have access not only to museum spaces and expertise but also to a pipeline of artifacts: “hundreds of artifacts” move between storage and the school each year through an artifact-loan process.

Students begin curating in seventh and eighth grade and, by high school, can take a curation class where they meet with museum curators and designers, learn about exhibit design, and “become the curators” telling their own stories.

What’s especially compelling for educators outside the Museum School is how the model radiates outward: the museum translates that learning experience into a curation summer camp so students beyond the school can learn to build an exhibit and tell a story through objects.

What’s next: redesign, capacity, and the river as an outdoor classroom

Sometimes the biggest barrier to learning is painfully unglamorous: lunch.

Ogren notes that GRPM serves about 40,000 students annually, and on busy days, the museum caps group visits at 500 to 600 students to protect the quality of the experience for school groups and the public.

The main bottleneck isn’t educational programming; it’s a lack of space for groups to gather, store coats and supplies, and eat lunch, which at times forces school groups to eat in classrooms or even in exhibits, limiting what museum staff can run.

A new west entry under construction will create a dedicated gathering area that can seat up to 200 students, provide a home base, and allow timed lunches, which will dramatically increase capacity and reduce stress for teachers.

And then there’s the riverfront, where education becomes tactile again.

Ogren lights up describing an upcoming outdoor classroom where, instead of staff gathering river specimens to bring inside, students will have direct access to the riverfront. This will allow hands-on learning experiences, such as collecting bugs, algae, fish, and other critters along the rocks, and observing the ecosystem firsthand.

She also points to bird-watching programs, noting that from the museum, you can see 30-plus bird species along the Grand River.

Ogren emphasizes expanding inclusivity through interdisciplinary learning. She notes that not everyone considers themselves a “science person,” but integrating science and art at the museum encourages more learners to engage. An example is a riverfront activity combining watercolor painting with observation skills: when painting a river critter, one must notice fins, legs, and shape – learning biology through focus and creativity.

For educators, the message is clear: the Grand Rapids Public Museum is more than a destination. It’s a partner and a hub for curiosity, making learning visible, immersive, culturally relevant, and shared. For students unsure whether Grand Rapids is “their” community, a visit to the museum can affirm that their story belongs here, too.

Photos by Tommy Allen and courtesy images of GRPM.

This story is part of the Bridge to Community Curiosity, underwritten by the Grand Rapids Public Museum. Through this partnership, we highlight GRPM’s mission to inspire curiosity, deepen understanding, and foster belonging by showcasing the transformative power of arts and education in West Michigan.